An interview with Philippe Cornu

Written By Translation Committee

Blog | Reflections on translation

Here is An interview with Philippe Cornu conducted by the Translation Committee’s junior translators Gregoire and Paul over a cafe gourmand.

An Interview with Philippe Cornu (1)

The young translators on the Dzogchen Today! translation committee asked questions about translation and the background knowledge needed to practice it. And Philippe Cornu, our senior translator, kindly took the time to answer over lunch at La Liberté restaurant. So this transcript may contain a few fork taps, for which we apologize… Dessert was the usual gourmet coffee, but it was Philippe’s words that really got us talking.

GRÉGOIRE

What do you have to pass on to the younger generations? What have you learnt from all this time spent translating Dzogchen texts? What would you like to pass on to us?

PHILIPPE

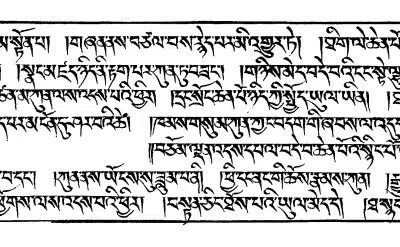

It is already a question of understanding what the Dzogchen is telling us. From the point of view of transmission through translation, the terms must be clarified by understanding them for what they are in the source language, in order to be able to restore not only the formal dimension but also the performative dimension in the target language. The peculiarity of Dzogchen texts is that they are performative.

GRÉGOIRE

Isn’t this the vocabulary work we started with the Dzogchen Today! Translation Committee?

PHILIPPE

Yes, exactly. For it to be performative, the breath of the text must be present. So there are two aspects: firstly, the formal aspect, which consists in translating the terms as accurately as possible, knowing that there are possible variations of the same term because of the diversity of semantic fields according to the context; secondly, the aspect of rendering the text into French, that is, the work of writing, which must allow an inspiring and direct access to the person who receives the text. This is not an easy task because we do not necessarily have a perfect realization of Dzogchen.

GRÉGOIRE

We, the young translators, are learning Tibetan, and we have some knowledge of Sanskrit. Do you think we should deepen our knowledge of Sanskrit? Or should we rather look at the archaic Tibetan terms in the texts of radical Dzogchen?

PHILIPPE

It is interesting to note that Tibetan has not changed much since the ancient period [1]: there are just a few orthographic and grammatical variations. Tibetan was fixed quite quickly when written Tibetan appeared.

PAUL

There is the reform of Tibetan orthography during the ancient period which effectively fixed things [2].

(…) but in Dzogchen there are many terms that have not been translated from Sanskrit, that appear in Tibetan without an equivalent…

GRÉGOIRE

Could you give us some examples of the differences between the Bön and Nyingma Dzogchen texts [3]?

PHILIPPE

From the Dzogchen point of view, it is interesting to note that even the classical vocabulary that has passed into the Buddhist schools has, I think, been influenced by the Dzogchen view. The typical example is “sangye” (sangs rgyas) which translates as “buddha” (which in Sanskrit simply means “awakened”) and which here means “purified” or “pure” for “sang” (sangs) and “fully developed” for “gye” (rgyas). If we take it from a purely gradualist point of view, it is purely Buddhist, because we will say that it is purified of all the veils and disturbing emotions and that at that moment, Buddhahood can blossom and manifest fully. But if you look at it from a Dzogchen point of view, it’s simply “kadak” (ka dag), primordial purity, and “lhundrup” (lhun grub), spontaneous perfection. So I suspect that they choose the term “sangye” to translate “buddha” because there were Dzogchen viewholders, the ancestors of the Nyingmapas in the 8th century. And it is the same with “changchoup sem” (byang chub sems): certainly, when translating a Tibetan text coming from Mahayana Buddhism, you have to translate “mind of awakening”, bodhicitta in Sanskrit; but for Dzogchen, it is “pure and perfect mind”, which also refers to primordial purity and spontaneous presence.

GRÉGOIRE

Are these really your own personal creations and reflections?

PHILIPPE

Actually, it’s also a reflection on the Bönpos, because they’re not supposed to refer to Sanskrit sources, but they use the term “changchoup sém” much more than the Nyingmapas. They even use it more than “rigpa” (rig pa). Because there is an archaic aspect to Bönpo Dzogchen in terms of terminology, choices have been made, and contrary to what the historiography tells us, which tries to create a rivalry between the Bönpos and the Buddhists of the time, I think there are many who have collaborated.

PAUL

Yes, Drènpa Namkha, Bairotsana…

PHILIPPE

… who were on both sides! I think there were collaborations in forging terms. That’s interesting! These are Sanskrit terms that have been translated in a particular way, but in Dzogchen there are many terms that have not been translated from Sanskrit, that appear in Tibetan without an equivalent…

GRÉGOIRE

… without necessarily coming from earlier languages or other regions? The language of Zhang Zhung [4] for example?

PHILIPPE

There are certain terms that can be attributed to the Zhang Zhung language that is now attested. It is a true language, whereas in the past it has often been questioned by saying that it is a reconstruction. But it is not a reconstruction, there really is a vocabulary of Zhang Zhung that has been forged. Sometimes it can be compared to the vocabulary of Kashmiri Tantric Shivaism, but not always.

Philippe Cornu

GRÉGOIRE

Do you have an example?

PHILIPPE

There are analogies… For example, we speak of “sounds, lights, rays”, a vocabulary that really comes from the bönpos; but “sound” brings to mind the Shiva term “spanda“, the primordial vibration that comes from “paramashiva“, the Supreme Shiva.

GREGOIRE

In fact, the translation process has to take into account the potential influences of several traditions and practices.

PHILIPPE

You have to remember that it was yogis who exchanged information and vocabulary.

PAUL

During the reign of Trisong Détsèn, the Tibetan Empire was very large and there was a lot of traffic on the trade routes. It is also known that some of the translators were not always born in central Tibet, for example Yeshe De [5] was from Samarkand. So the linguistic knowledge of the translators was probably more extensive than we think.

GREGOIRE

In the modern world, we are used to making very clear distinctions between traditions: there are “Christians”, “Muslims”, “Hindus”… and we don’t see enough of the potential bridges between all these traditions.

PHILIPPE

Whereas if you go to Nepal, you can see that the places are Hindu and Buddhist, dedicated to Guru Rinpoche and Shiva… and Guru Rinpoche, if you look closely, has Shiva attributes! So the choice of translation is influenced by many factors!

End of the first part of the interview.

[1] 8th century

[2] Translators reformed Tibetan spelling to simplify and standardize it in 816 during the reign of Senaleg (Wylie: Sad na legs). They set the standard for what came to be known as classical Tibetan.

[3] The Bön and Nyingma Dzogchen are the two distinct lineages of the Great Perfection of the great Tibetan traditions: the Bön tradition originates from Master Tönpa Shenrab Miwo and is dated to about two thousand years before our era. But the dates vary between sources. See for instance : John V. Bellezza, gShen-rab Myi-bo. His life and times according to Tibet’s earliest literary sources. The Nyingma tradition originates from the master Garab Dorje and is dated around the first century AD. But here again the dating varies. See for exemple, among others : John M. Reynolds, The Golden Letters. The Tibetan Teachings of Garab Dorje, First Dzogchen Master, Snow Lion, 2012.

[4] The ancient kingdom of Zhang Zhung, the cradle of the Bön tradition, corresponds to the current regions of Ngari and Ladakh (Western Tibet). For more details, read: Chogyal Namkhai Norbu & Donatella Rossi, A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, volume 1, The Early Period, North Atlantic Books, 2013.

[5] A very important translator who translated more than 300 texts of the Buddhist tradition.

More Posts on Translation

The Pure and Perfect All-Encompassing Mind

“The Pure and Perfect All-Encompassing Mind” is a new translation from the Dzogchen Today! Translation Committee. Enjoy!

The Perfection that cuts through everything

“The Perfection that cuts through everything”, is a new translation from the Dzogchen Today! translation committee.

The Pure and Perfect Mind, light of the three dimensions of existence

“The Pure and Perfect Mind, the Light of the Three Dimensions of Existence” is a new text translated by the Committee.