The Four Testaments of the Vidyādharas

Written By Grégoire Langouet

History of Dzogchen

This article presents the Four Testaments of the Vidyādharas, essential teachings from the early masters of Dzogchen.

Series: The Lineage

The ancient lineage

The Four Testaments of the Vidyādharas (Rig ‘dzin gyi zhal chems bzhi) [1]

These are the essential and “posthumous” teachings of the first four Dzogchen masters. Although these texts are found in the man ngag sde collections, their traditional presentation makes them the final teachings of the most ancient practitioners, and attributes them to Vimalamitra [2]. Their presentation is essential to the Dzogchen View.

These therefore include first and foremost the Three Aphorisms that Garab Dorjé transmitted to Mañjuśrīmitra. According to the Lo rgyus chen mo [3], Mañjuśrīmitra then divided the three aphorisms into three series:

- Semdé (Tib.: sems sde) for those whose minds are already calm;

- Longdé (Tib.: klong sde) for those who are beyond action;

- Men ngag dé (Tib.: man ngag sde) for those concerned with direct instructions.

He wrote them down and hid them under a rock shaped like a double vajra. In the middle of a mass grave, surrounded by countless dākinīs and frightening creatures, he remained in contemplation in a state of equanimity for 109 years, according to the text. Mañjuśrīmitra disappeared like his master, in a sphere of rainbow light. In turn, he left his last testament to his main disciple Śrī Siṃha (Shri Singha; Tib.: Dpal gyi seng ge), entitled the “*Six Experiences of Meditation”* (Sgom nyams drug pa). When Śrī Siṃha manifested his body of light, he in turn entrusted his testament known as the “Seven Nails” (Tib.: Gzer bu bdun pa) [4] to Jñanasūtra (Tib.: Ye shes mdo), . He also left this world by disappearing into a sphere of light, leaving to his disciple Vimalamitra his own testament, the “*Four Contemplative Methods”*, or Four Ways of Abiding (Tib.: Bzhag thabs bzhi pa).

“According to the tradition, these oldest transmissions are immediate and contain the full depth and richness of the countless Dzogchen lineages that have flowed from them ever since—right up to the present day.”

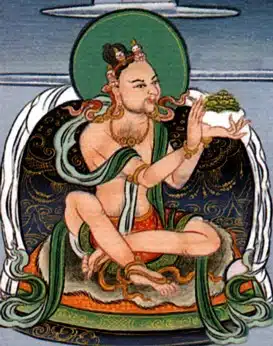

Śrī Siṃha

After Garab Dorjé’s first testament, the Three Aphorisms, Mañjuśrīmitra passed on the second, the Six Meditative Experiences (Sgom nyams drug pa) [5], to Śrī Siṃha. Dealing directly with contemplative practice, the essence of these six points can be summarised as follows:

“O son of noble family, if you wish to experience the continuity of naked primordial awareness:

- Concentrate on the ultimate sphere of primordial awareness (Tib.: rig pa’i chos dbyings) as your object (the pure sky).

- Compress the body’s points (through posture) [6].

- Close the doors of going and returning (breathing).

- Focus on the target (the ultimate sphere).

- Rely on the immutable (body, eyes, and wisdom).

- Grasp the vast immensity (the nature of wisdom itself).

Of course, this type of text requires oral transmission from a qualified master of an authentic lineage in order to be put into practice. Without explanation and commentary, it remains relatively obscure, as we can see from reading it.

Jnanasutra

The following testament is that of Śrī Siṃha, and was transmitted to Jñānasūtra. Once again, the focus is more on the View than the “practice” itself. The Seven Nails (Gzer bu bdun pa) [7] are as follows:

- Nail (fix, strike) (gzer) saṃsāra and nirvāṇa together by means of clear primordial knowledge, penetrating lucidity.

- Nail the observer (Tib.: sems) and the observed (Tib.: yul) together with the help of the self-arising lamp.

- Nail mind (Tib.: blo) and tangible phenomena (Tib.: dngos) together with the help of pure natural essence (Tib.: ngo bo rang dag).

- Nail nihilism (Tib.: chad) and eternalism (Tib.: rtag) together by means of freedom from all views.

- Nail phenomena (Tib.: chos can) and the nature of phenomena (Tib.: chos nyid) together using primordial non-phenomenal evidence (Tib.: rig pa chos min).

- Nail torpor (Tib.: bying) and agitation (Tib.: rgod) [8] together with the liberation of the sense faculties.

- Nail appearances and emptiness together by means of the primordially perfect Body of Reality. [9]

In the full text, the meaning of the initial presentation is clarified by seven metaphors that reinforce the seven nails. The text’s fundamental intention is clear: to aim beyond all duality. It is a matter of “nailing together” what we have become accustomed to separating and discriminating as being different. This involves going beyond false views (Tib.: log lta)—including those of the two extremes (Tib.: mtha‘ gnyis), mentioned in the fourth nail—in order to arrive at a correct, authentic, and therefore non-dual view.

Vimalamitra

Finally, the fourth and last testament is transmitted by Jñanasūtra to Vimalamitra. It is entitled *The Four Means of Abiding (*or Ways, Methods) (in Contemplation) (Tib.: bzhag thabs bzhi pa) [10]. Here is an excerpt:

“How wonderful! If you practice this continuously, joy will arise naturally. Listen! If you wish to attain the state of continuous contemplation (Tib.: ting nge ‘dzin) of great equality, practice abiding without distraction, day and night, in reality as it is (Tib.: de nyid):

- If you wish to practice in all activities, maintain all appearances in the correctness of direct contemplation of vision.

- If you wish to master the direct instructions that strengthen your meditation, remain in the unity of mind and tangible phenomena, through the awakened presence of natural contemplation like the ocean.

- If you wish to attain natural liberation from all views, bring phenomena to cessation through the natural vision of mountain-like contemplation.

- If you wish to remain naturally in the attainment of all realizations, remain in the basis, the three Bodies, and naturally liberate all confusion through the direct instructions on the view of primordial obviousness contemplation.”

Thus was stated the last of the four testaments of the Vidyādharas, which allowed for the direct and complete transmission of the essence of Dzogchen. According to the tradition, these oldest transmissions are immediate and contain the full depth and richness of the countless Dzogchen lineages that have flowed from them ever since—right up to the present day. The fact that transmission subsequently became mostly “gradual” (as with the four initiations of the Vajrayāna) does not prevent the continuity of the immediate transmission of the Vidyādharas, still today—and perhaps tomorrow.

[1] Or the Four Posthumous Teachings (or last words) of the vidyādharas (rig ‘dzin gyi ‘das rjes bzhi). BACK

[2] These texts can be found in the Bi ma snying thig, in the Golden Letters’ section (gser yig can). They are said to have been compiled by Vimalamitra in the 8th century. Historical criticism dates them much later, namely after the 11th century at least. The versions available today also owe much to the compilation work of Klong chen pa. The critical editing of these short texts and their precise dating and transmission therefore remains to be done. Jean-Luc Achard has provided a French translation in Les testaments de Vajradhara et des porteurs-de-science (The Testaments of Vajradhara and the Bearers of Science), Paris, Les Deux Océans, 1995. BACK

[3] Snying thig ya bzhi, vol. 9, Trulku Tsewang, Jamyang and L. Trashi (eds.), New Delhi, 1971. A partial translation can be found in Jim Valby, The Great History of Garab Dorjé, Manjushrimitra, Shrisingha, Jnanasutra and Vimalamitra, Arcidosso, ed. Shang Shung, 2002. BACK

[4] On this subject, see the interesting article by Georgios T. Halkias, “Śrī Siṃha’s Ultimate Upadeśa. Seven Nails that Strike the Essence of Awakening,” in Illuminating the Dharma: Buddhist Studies in Honour of Venerable Professor KL Dhammajoti, Toshiichi Endo (ed.), Centre of Buddhist Studies, University of Hong Kong, 2021, p. 181-194. BACK

[5] According to the version found in ‘Jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha’ yas, “’Jam dpal bshes gnyen gyi zhal chems sgom nyams drug pa,” in Gdams ngag rin po che’i mdzod, 18 vols., Delhi, Shechen Pub., 1999, vol. 2, p. 9-11 (folios 5a3-6a6). BACK

[6] This concerns the six objects of consciousness (Tib.: yul drug): forms (Tib.: gzugs), objects of the visual sense; sounds (Tib.: sgra), objects of the auditory sense; smells (Tib.: dri), objects of the olfactory sense; tastes (Tib.: ro), objects of the sense of taste; contacts (Tib.: reg), objects of the sense of touch; and phenomena (Tib.: chos), objects of consciousness. BACK

[7] “ShrI siM ha’i zhal chems gzer bu bdun pa,” in Snying thig ya bzhi, 13 vols., Delhi, Sherab Gyaltsen Lama, 1975, vol. 3, p. 318-324; see also the version “ShrI siM ha’i zhal chems gzer bu bdun pa,” in ‘Jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha’ yas, Gdams ngag mdzod, Bkra shis dpal ‘byor (ed.), 18 vols., Paro, Lama Ngodrup and Sherab Drimey, 1979-1981 (BDRC W20877), vol. 2, pp. 11-13. BACK

[8] “Depression and ecstasy” is suggested by Mila Khyentse Rinpoche, in a more “contemporary” manner. BACK

[9] French translation modified from a version by Mila Khyentse Rinpoche; Another english translation can be found in Georgios T. Halkias, “The Seven Nails: Śrī Siṃha’s Ultimate Upadeśa,” p. 187-188: “[1] Strike the interval between saṃsāra and nirvāṇa with the nail of primordial wisdom’s unobstructed luminosity. [2] Strike the juncture between knower and its object with the nail of self-arising light. [3] Strike the duality between mind and matter with the nail of self-purified essence. [4] Strike the division between affirmation and negation with the nail of [gaining] utmost freedom from views. [5] Strike the juncture between subjects [phenomena] and their nature with the nail of intrinsic awareness of the dharmatā. [6] Strike the interval between dullness and agitation with the nail of the five sense doors [resting] in utter relaxation. [7] Strike the distinction between appearance and emptiness with the nail of the primordially perfected dharmakāya. ” BACK

[10] “Ye shes mdo’i bzhag thabs bzhi,” in Klon chen rab ‘byma dri med ‘od zer, Gsung ‘bum, 26 vols., Beijing, Krung go’i bod rig pa dpe skrun khang, 2009 (MW1KG4884_6A0690), vol. 1, p. 211-214, p. 212. BACK

More Posts

The Supplication that Fulfills All Wishes

In “The Supplication that Fulfills All Wishes”, Mila Khyentse gives us a prayer from his Master for difficult times and conditions.

The Fourth Time

In the article ” The Fourth Time ” , Johanne talks about the three times… and the fourth one, beyond time.

A Dream Life

In « A Dream Life », Grégoire wonders what the “right conditions” would be for practicing a spiritual path.